In March 2016, my husband and I went on a holiday together to Tasmania for five nights. It was the first time we’d left our young children for more than a night. My parents stepped up to mind them.

In March 2016, my husband and I went on a holiday together to Tasmania for five nights. It was the first time we’d left our young children for more than a night. My parents stepped up to mind them.

The occasion was my 40th birthday and Tasmania was a ‘bucket-list’ destination. The scenery, the food, MONA – it seemed to have it all – everything, that is, except for perfect weather.

One of the highlights of our Tassie trip was to be an adventure boat cruise along the dramatic south east coast. But on the morning of the designated trip, we woke to a cool winds and drizzle. The tour operator rang. With three metre swells buffeting the coast, the cruise was not to be.

At that point, we started looking for other options. We nearly hired a car. Nearly booked a bus tour. Nearly went for a walk. But ended up doing none of those things.

Instead, with drooping shoulders, we decided to check out the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. There was an exhibition on about women who’d migrated to the state between 1945 and 1975.

To say that I was unprepared for the emotional power of what we experienced is an understatement. The exhibition was wonderful. Not only had the curators sourced wonderful photos and ephemera of the period, they’d actually recreated whole rooms of a house – a kitchen, a bedroom, and a 1950s sitting room complete with a chaise lounge where you could sit and leaf through photo albums.

But there was one story that particularly caught my eye. It was the tale of two Calabrians, Gilda and Vincent Fabrizio.

In the 1950s, Vincent, had come to Tasmania to work on the hydro. Gilda was back in Italy, living in a nearby village. When they married, the couple had never met. The wedding took place ‘by proxy’, a not uncommon practice in the post-war years where couples could marry ‘in absentia’ with a stranger standing in for the bride or groom.

Gilda’s family encouraged her to send a photo of herself. Vincent did likewise, hiring a suit and travelling into a Hobart photographic studio. When Gilda arrived in Tasmania, she came bearing a dinner set given to her by her in-laws. In the intervening years, only the tureen had survived.

Vincent and Gilda’s tale was a short story waiting to be written. When I got home, I wrote it, re-imagining that scene on the dock where the couple (Rosa and an un-named husband in my story) meet for the first time.

Some short stories are a battle. Every word, every sentence is hard-fought. ‘By Proxy’ was not that kind of story. The words and scenes came easily. It did not take too many drafts.

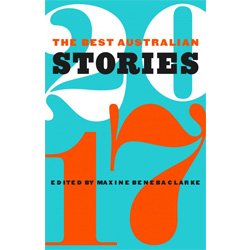

When I got the email from Black Inc to let me know that ‘By Proxy’ had been chosen for The Best Australian Stories 2017, I was shocked. That a writer of the calibre of Maxine Beneba Clarke had seen fit to select it alongside short stories from Australia’s pre-eminent writers was humbling and surprising.

I still can’t quite believe it.

I blink, and my name is still there.

To Vincent and Gilda, thank you.

For more information, or to purchase a copy of Best Australian Stories 2017, visit Black Inc.

Congratulations. You must be so proud!